The Uncertain States of America Reader

Book,Introduction to The Uncertain States of America Reader (Sternberg Press, Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Serpentine Gallery, 2006). I co-edited this book, and co-authored the introduction, with Noah Horowitz.

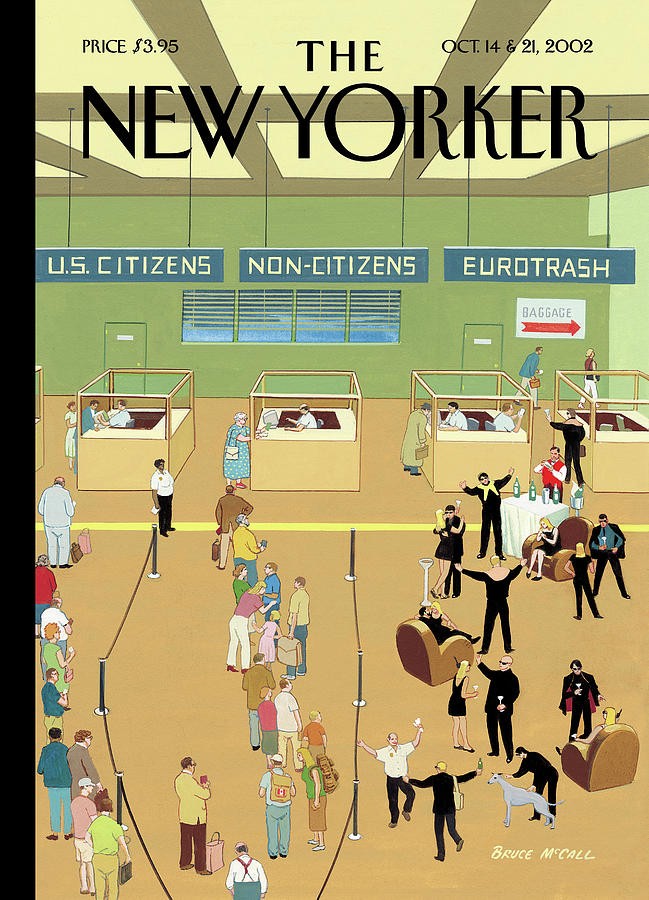

This reader, a companion volume to the “Uncertain States of America” exhibition catalogue, began in 2005 when the curators met with artists in their studios. What were the artists reading? What articles, books, reviews—and, they soon discovered, cartoons, cookbooks, memoirs, and film scripts—were influencing their practices? A comprehensive survey of these curiosities was not included in the earlier exhibition catalogue. It remained, pace Obrist, an “Unrealized Project.”

Invited one year later by the curatorial team to construct such a list, we began by surveying the artists in the show and using their recommendations, many of which are included in the reading list at the back of this book, as a starting point for the selection of texts presented here. What follows is a synthesis of their nominations and our own research into significant recent writings by American artists and critics on artistic practice and cultural politics in the United States today. Keeping with the theme of this exhibition, emphasis has been placed on identifying “young,” “emerging” writers, though salient pieces by those who reside outside of America are also included.

We hope that the following selections introduce some new writing and writers and shine a fresh light on more familiar passages. Equally, we hope that this books reception reaches beyond those audiences who experience the exhibition first hand, and that it becomes a conduit of knowledge outside the immediate exhibition-going public.

The present volume is not a “portrait of the exhibition’s artists in text” (an early, and mightily optimistic, vision). Nor is it a top-down survey of all that is novel and noteworthy in today’s art world. Cognizant of this exhibition’s ambitious modus operandi, to represent “a ‘new’ vision in American contemporary art,” we realize, of course, that some may view this publication as precisely a currency-enhancing invocation of already prevalent curatorial and critical interests. And we understand that such a publication indelibly sanctifies its content, that it operates as a value filter or, as Isabelle Grow observes in these pages, a “sound bite” in order to “underline claims for art-historical importance or theoretical erudition.” Yet it is our underlying hope that this anthology belies such a roll call of erudite endorsements and that its contents engage readers in unanticipated manners.

It is commonplace to note that contemporary art is swaddled in a haze of words and that it is futile to attempt a synoptic overview of art discourse, so we drew simple boundaries beyond which our inquiry would not trespass, several of them congruent with those set by the “Uncertain States of America” exhibition. The two most binding examples: each piece of writing included here has been published since 2000, and each discusses contemporary art, aesthetics, politics, or the amorphous and expansive zone where these three concerns overlap. Selecting texts thus became a game, albeit one burdened by methodological complications. How to accommodate writings both by artists in “Uncertain States of America” and others critical of their programs, or, for that matter, the very presuppositions of such a traveling group show? What, we contemplated, would be an appropriate framework to muster comprehensiveness in the face of mind-boggling pluralism and attendant information overload? How to play the game? One artist’s advice proved invaluable: “Comprehension and coherency are dead ringers for the longing for authority. Don’t be an authority. And don’t apologize for not being an authority.” So we aimed for an eclectic sampling of material by writers—art historians, journalists, critics, artists, philosophers, a graphic designer–slash-lawyer, as well as a fictional character devised by an artist collective—whose contributions, we felt, gained from their placement alongside one another and from being set in relief against the project as a whole.

In recent years, many have noted how fashionable art that addresses its broader social context has become. The translation of Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics into English in 2002 and the ongoing debate about this set of essays is one prominent example of this tendency. Others pertain to the intensification of discussion about the internet’s (virtual) social power and the agency of extra-gallery/museum practices, the latter of which inspired “The Interventionists: Art in the Social Sphere,” an exhibition curated by Nato Thompson and presented at MASSMoCA in the summer of 2004.

There has also been a notable upsurge of interest in the art world’s supposedly mutating structural composition. For example, while new technologies may enable individuals to act and transact at a distance, there has of late been a curious intensifying of interaction among buyers, sellers, enthusiasts, and pundits at international and ever-trendy art fairs, auctions, biennials, and symposia that now demarcate the art calendar as a matter of course. These developments have not ruptured the clout of cultural epicentres like New York or London, but they have hastened the transformation of how contemporary art’s specialist community of artists, dealers, curators, collectors, critics, administrators, sponsors, and policymakers do business: on the run and behind the veil of ever-more-elaborate VIP rituals. Such processes may have aided contemporary art’s ascension as a lifestyle commodity, but the pragmatic need to secure financing and visibility in this competitive economy of symbolic goods and services arguably exposes it to opportunism and instrumentalization as never before. The lamented “crisis” of contemporary criticism is at least partially a result of this change: How does one distinguish among so many exquisitely manufacture and seamlessly managed products?

The writings by Jack Bankowsky, Andrea Fraser, Matthew Jesse Jackson, Miwon Kwon, Robert Morris, and Julian Stallabrass included here explore various aspects of these developments, and their reverberations are palpable elsewhere in this volume and in much of today’s broader cultural discourse. Book titles such as Art, Money, Parties (2004) have thus come to embody the preconditions of this moment, while “Arty Party,” Hal Foster’s review of Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics and Postproduction (2002) and Obrist’s Interviews: Volume I (2003), offers not only a cogent reading of these three publications but also an instructive (if glib) synopsis of today’s art world at large: “Apparently, if one model of the old avant-garde was the Party à la Lenin, today the equivalent is a party à la Lennon.”

Despite appearances to the contrary, the fundamental nature of art production remains largely intact: artists still create, patrons still collect, and critics still critique. Yet some accentuations within this value chain do indeed appear to be novel (or at least more apparent): the art industry’s privatization and its (at times) politically suspect diffusion into developing economies offer two prominent cases in point. Echoing Bankowsky, one might say that today’s art is just more: more visible, more mediated, more spectacularized, more institutionalized, more scrutinized, more expensive, more profitable, and more “global.” “The international Guggenheim conglomerate isn’t so much ‘McMuseum,’” Peter Plagens elsewhere reflects, “as it is Boeing or General Dynamics—contemporary art on a military-industrial scale.”

Buttressing these developments is an attenuation of interest in specific regional activities. On one level, this is a natural byproduct of the exhibition industry’s globalization, whereby biennials, project spaces, and conferences from Cuba to Korea take local socio-political contexts as points of departure. Equally, this interest in the regional appears to constitute the inevitable flip side to 1990s-era globalization hyperbole, with the now hackneyed promises of multilateral cultural exchange replaced by more nuanced readings of these processes’ complexities (as epitomized in the five “platforms” of Documenta XI, 2001–02). Whatever its roots, the increasing attention focused on artistic proceedings outside of traditional Western art centers is having a formidable impact in the classroom, salesroom, and across tireless rumor mills; as in other industries, China, Russia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East have become pivotal foci of speculation.

Counterbalancing this trend—and following in the wake of 9/11 and the 2004 re-election of George W. Bush—is the zeroing in of (primarily European) interest in American art and artists. In the past year alone, one could cite “Uncertain States of America,” “USA Today” at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, “This Is America: Visions of the American Dream” at the Centraal Museum in Utrecht, the Netherlands, and even “Day for Night,” the 2006 Whitney Biennial (curated by Chrissie Iles and Philippe Vergne, European curators now ensconced in American institutions).

Any cross-cultural interpretation is bound to create misunderstanding, and surely each of these exhibitions draws a limited portrait of the culture it seeks to portray. A somewhat atypical example, “The American Effect: Global Perspectives on the United States, 2000–2003,” held at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2003, exemplifies the dangers inherent in such projects. While many of the above exhibition organizers are one step removed from their subject matter—in the center looking at a periphery, or vice-versa—a two-step removal marked the organization of “The American Effect,” in which an American curator, Lawrence Rinder, traveled outside of the country to find artists whose art critiqued the United States. The resultant exhibition was, in the words of one reviewer, “hectoring and jejune and did little to advance the terms of that encounter.”

This is undoubtedly a moment marked by a serious interest in the actions America is taking on the world stage—actions that have been described as a cause for grave concern. We do not attempt to authoritatively engage those concerns here. We do, however, think that this sampling of discourse by and about a country’s visual artists leads to insights about its politics and society not gained elsewhere.

Many of the artists in this reader’s eponymous exhibition would, of coure, be quick to disavow explicitly political readings of their work, preferring, as Kori Newkirk recently stated during a panel discussion at Bard College’s Center for Curatorial Studies, to “seduce first.” He continued: “‘Political’ content can [simply] come in through the side door or window.” The art world’s definition of the term political remains fuzzy (as Pamela M. Lee rightly notes of its definition of globalization as well), but, on occasion, this thinking-through-form counters the obfuscation that now stands for contemporary American political discourse. At the very least, it gives a sense of what it is like to live in the United States today, and results in some inspired debate. We hope that this book serves not only as a valuable compendium of recent writing about contemporary art but also as inspiration to seek further understanding of these “Uncertain States.”

We would like to thank Julia Peyton-Jones, Daniel Birnbaum, Gunnar B. Kvaran, and Hans Ulrich Obrist for inviting us to undertake this project and for being instrumental in its realization; Caroline Schneider of Sternberg Press for ably seeing the book into print; the artists for their consistently trenchant criticisms and honest responses; all of the authors and publications who granted reprint permission; Charles Gute and Nicole Lanctot for their unflagging copyediting efforts; and David Reinfurt and Stuart Bailey of Dexter Sinister for their grace under pressure. Likewise we wish to thank Greg Allen, Eric C. Banks, Christopher Bedford, Tom Eccles, Bettina Funcke, Liam Gillick, Rachel Harrison, Michael Ned Holte, Gareth James, Miriam Katz, Molly Nesbit, Lauren O’Neill-Butler, Scott Rothkopf, and David Velasco for their thoughtful contributions to the dialogue that produced this book.