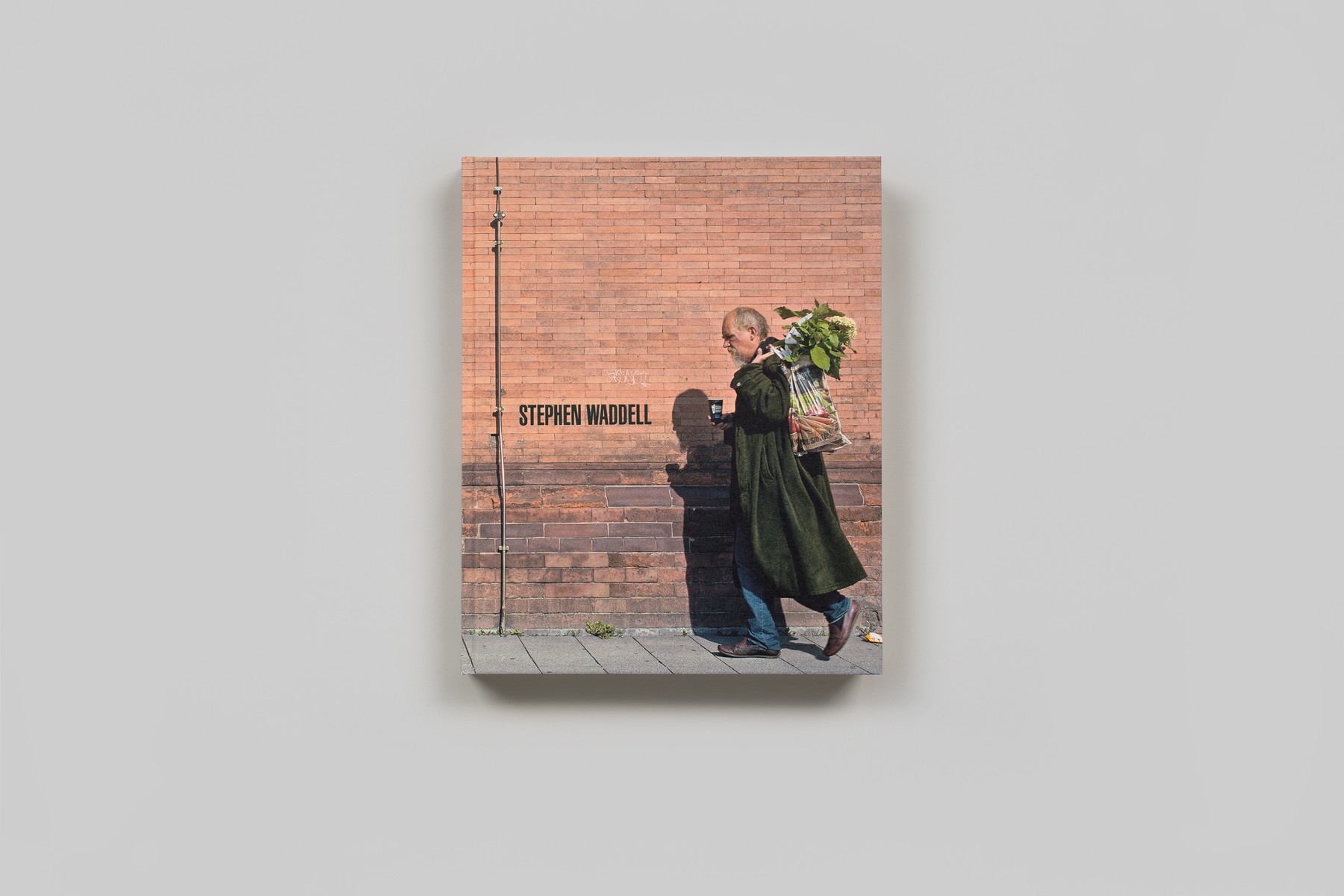

Stephen Waddell

Writing,I served on the jury that awarded Stephen Waddell the 2019 Scotiabank Photography Award and was honored when he later invited me to contribute to the book occasioned by the prize. The book was published in Spring 2020 by Steidl and can be ordered online. This is an excerpt from the beginning of my essay.

We’re surrounded by potential pictures, but it can be hard to see them. I don’t refer to the torrent of images in our social-media feeds, but rather to the world itself, especially the urban world. It is full of scenes worth noticing, and people worth photographing, that we can’t or won’t take the time to appreciate. This is partly a matter of survival. Writing in Berlin more than one hundred years ago, sociologist George Simmel noted that “the metropolitan type of man … develops an organ protecting him against the threatening currents and discrepancies of his external environment which would uproot him.” Unlike rural communities, Simmel argued, where meaningful relationships develop slowly over time and are reinforced by repeated interactions, burgeoning cities required residents to develop defense mechanisms. Simmel’s Berlin was made up of small villages rapidly being drawn together, by transit and by industry, and by the time he wrote, in 1903, it seemed as if its citizens were thrown into new combinations every hour. These many chance meetings, he reported, created mental habits characterized by “reserve.” People doled out sympathies to each other in varying degrees, careful not to overextend their emotions as they adjusted to the accelerating pace of urban life. The city left its imprint on people’s behavior.

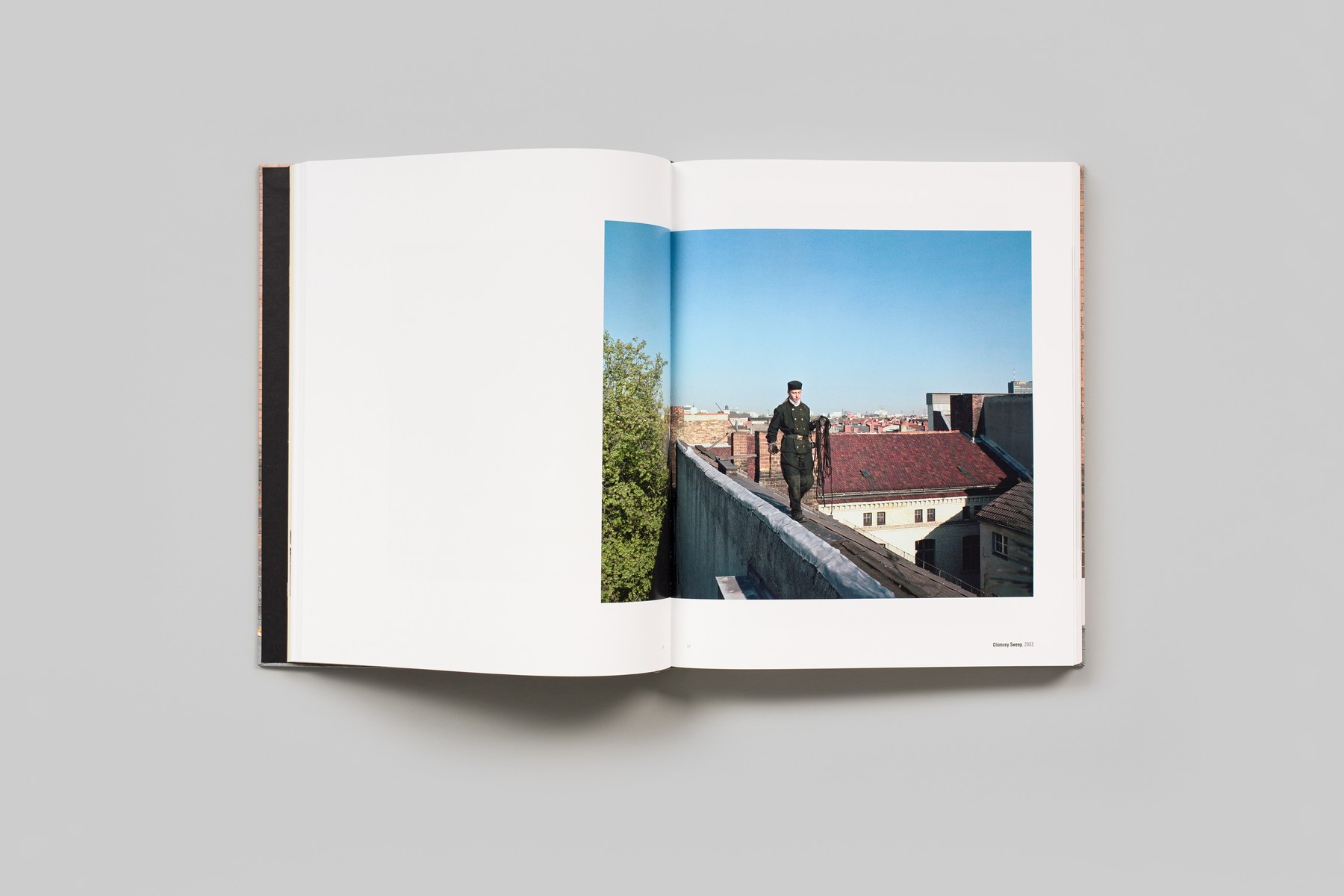

Simmel’s use of the term reserve comes to mind when Vancouver artist Stephen Waddell describes his own photographs, mostly made in urban public spaces, as austere. “The subjects I choose, how I shoot them, and how I scale the prints,” he suggests, all contribute to this effect. Most depict a single person or a small group of people. These subjects rarely acknowledge the camera and are often absorbed in the activity, whether labor or leisure, that has brought them before Waddell’s lens. Vanishingly few are granted names. They are identified instead as types: Wader (2006); Man Sketching (2004); The Collector (2016); Two Women (2014). The people in Waddell’s photographs therefore become allegorical figures that stand in for us and represent broader acts of human striving—the ways we stumble through, toil away, try to enjoy, and otherwise spend our time in everyday life. “Without the human struggle,” he says, “I don’t know if I would make photographs.”

There was a catch to Georg Simmel’s penetrating observations of mental frameworks in the swelling city: the “reserve” he identified only ran so deep. While urban communicative life “rests upon an extremely varied hierarchy of sympathies,” he writes, “the sphere of indifference in this hierarchy is not as large as might appear on the surface.” So, too, with Waddell’s photographs. The austerity is an outward appearance; beneath it flourishes a rich humanism. That attitude is exemplified not only by his commitment to patient observation, a form of empathy not shared by every street photographer. It comes, too, from his extensive knowledge of, and deft positioning within, the tradition of realist picture-making.

Waddell’s conception of this tradition stretches back to Édouard Manet. Manet’s portraits were remarkable, in art historian Michael Fried’s view, for their active, explicit engagement with the art of the past, for their presentation of that engagement in a surprisingly flat style (for the 1860s), and for subjects who were notably unaware of the viewer by virtue of their “absorption” with something within the space of the painting itself. The mystery of this latter characteristic extends the viewers’ interaction with the artwork as they try to orient themselves and find a position within the image.

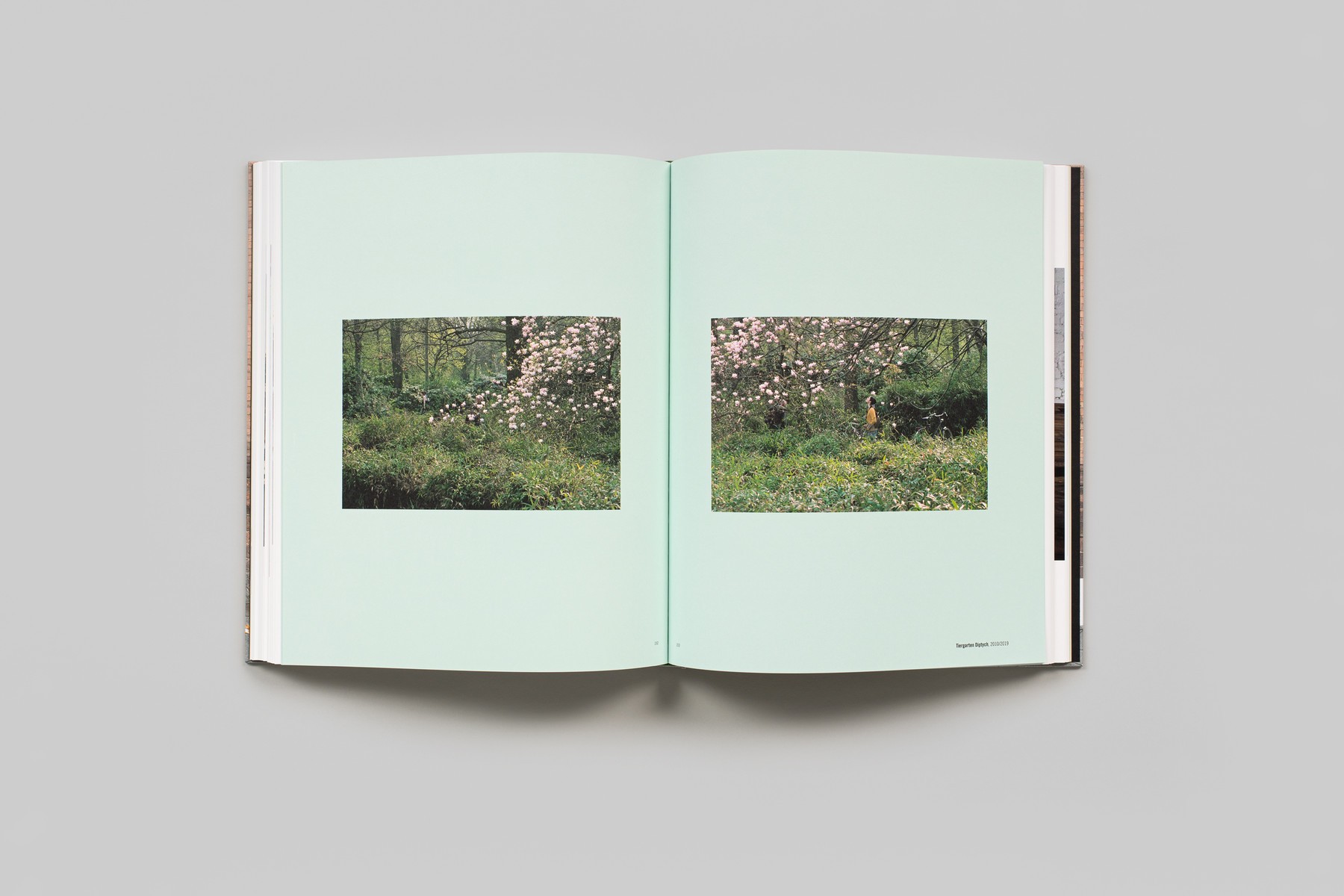

In photography, this tradition can be traced through the work of August Sander, Eugène Atget, Walker Evans, and certain street photographers who prowled American cities in the mid-twentieth century. More recently, Fried argues that contemporary photographers picked up the question of how an artwork addresses the viewer in the late 1970s and early ‘80s. As artist and writer Roy Arden has deftly argued, however, Waddell neither “accept[s] the haphazard, often surreal compositions” of street photographers like Garry Winogrand, nor will he “stage the image he would like to make” like some of the postmodern artists Fried champions. Instead, to get his pictures, Waddell must patiently “hunt them down.” This takes time and effort. He spends untold hours traversing cities on foot or in his car, gathering ideas for motifs to explore, scouting suitable locations to photograph them, then patiently waiting for the right moment to reveal itself. Sometimes, of course, a powerful scene presents itself as if by revelation—in those instances, Waddell must be ready.

To represent the complexity of humans in photographs, especially humans encountered only glancingly, you’re obliged to set aside preconceptions about them. And if you plan to work in a genre that critics often claim is exhausted, you’re also obliged to know your forebears’ work intimately. It is easy today to make photographs that mimic Atget or Evans. As Waddell puts it, “you have to find ways of revitalizing a tradition that are more than nostalgia or celebration.”

Waddell’s photographs, nearly always presented singly rather than in series, reinvigorate the tradition of figurative realism with uncommon frequency. “Almost every picture I make has some enigma or redirection in it,” he states, “whether people can articulate it or just feel it.” The initial impression of his pictures’ austerity belies a more intricate and paradoxical reality—his art models an unsentimental compassion for others.