Mårten Lange

Writing,Originally published in New Scandinavian Photography (Black Dog Publishing, 2015). Learn more about Lange by visiting his website.

The British writer Robert Macfarlane has spent several years collecting words that describe specific landscape features and effects of weather. The work confirmed for him this fact: “there are experiences of landscape that will always resist articulation, and of which words offer only a distant echo. Nature will not name itself. Granite doesn’t self-identify as igneous. Light has no grammar.” Light may not have a grammar, but what it communicates of the world can be captured. This is a task for photography. A camera’s lens grasps phenomena that escape words, and the most compelling photographs frame what we cannot easily describe. They succeed by containing within them an element of wonder.

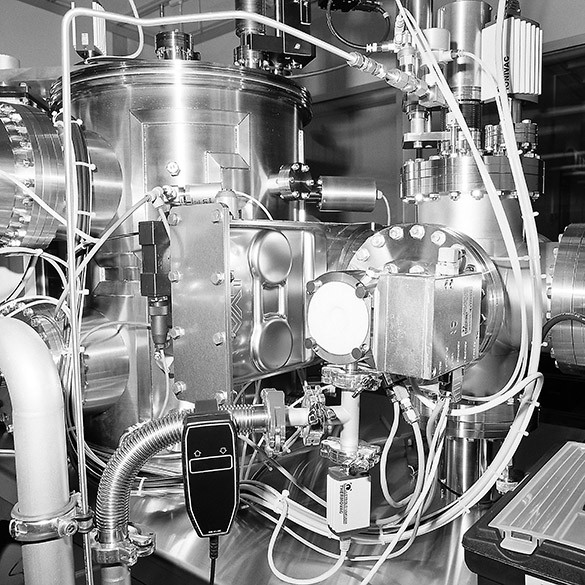

For nearly a decade, Swedish artist Mårten Lange has recorded such mysteries, whether working in places best described as natural or man-made. (Today the two are always intermingled.) Lange’s 2007 series Machina explored scientific laboratories—perhaps the ultimate man-made territory. Focusing upon machines at Gothenburg University, his close-up views depict—in great detail—tubes, wires, bolts and canisters. These devices extend our ability to comprehend the natural world, so it is appropriate that everything is brightly lit and in sharp focus. What is left unrecorded by Lange’s lens, though, is the purpose of these machines. What are they for? The viewer’s imagination must step in and guess what the tangle of wires allow scientists to see.

So, too, must the imagination aide understanding of Another Language, the most succinct and compelling expression of Lange’s aesthetic to date. The fifty-nine black-and-white images in this diminutive 2012 book have simple compositions. He has placed the subjects of the pictures in the centre of each frame. Yet those subjects range widely, and the scale of what is depicted shifts from macroscopic to microscopic. This often happens from one image to the next; a frozen lake, seen from an airplane, appears opposite a small fossil.

Every image in the book is the same size, and a lack of contextualizing information—such as horizon lines—further flattens hierarchies. Animal, mineral, vegetable: all appear within Another Language’s pages without sharp distinctions. A viewer must rely on previous experience, on the mind’s catalogue of imagery, to disentangle these subjects and find their proper relationships.

Lange’s talent is to discover a separate reality in the surfaces of our world—even the impenetrable, glass-and-concrete facades of our cities.

Links among images are important to Lange. “Books are my primary interest and influence,” the artist has said. “I prefer intimately scaled printed matter, and I make my exhibition prints to match. If you want to see detail, you must look closely.” Lange’s clear vision descends in part from Scandinavian predecessors. His photographs recall the combination of specificity and mystery that characterizes the late Norwegian artist Tom Sandberg’s best work. And though people rarely appear in Lange’s pictures, as they do in Swedish photographer JH Engstrom’s work, Engstrom led a workshop that opened the younger artist’s mind to the expressive possibilities of the medium. (“I had never met anyone who thought about photography like he did,” Lange says.) His work is not as diaristic Engstrom’s, or for that matter Anders Petersen’s. Instead, Lange is closer in spirit to the Swedish photographer Gerry Johansson, whose pictures depict human culture through the traces it leaves on the landscape. Lange and his peers also rely more upon strategies derived from Conceptual art: categorization, systematization, emotional expressiveness nestled within a restrained style. Such impulses might also have come from Lange’s family history and education. His forebears were architects, engineers, and chemists, and Lange studied natural sciences and engineering until discovering photography while attending high school.

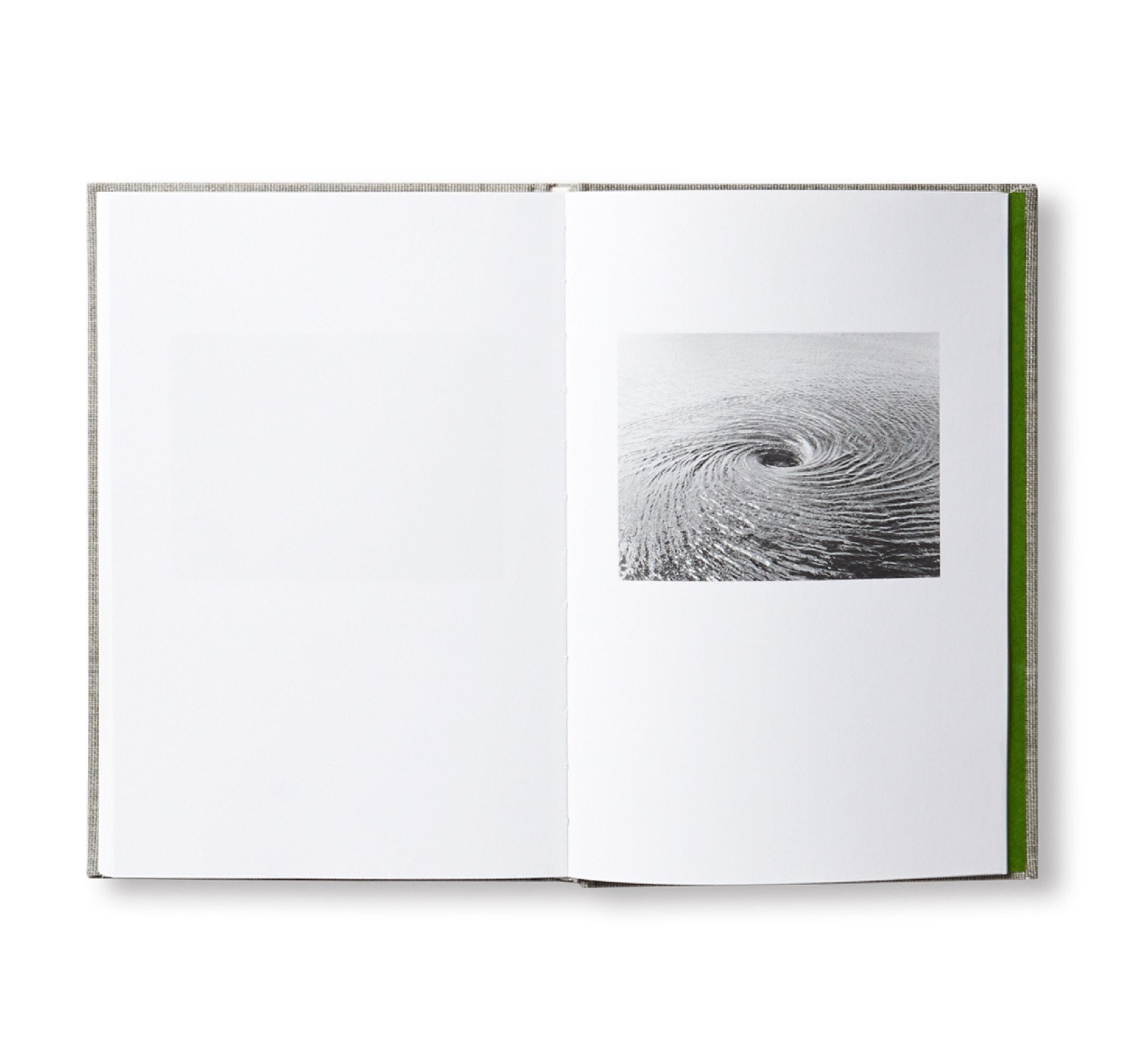

Lange likewise feels an affinity to German photographer Jochen Lempert’s studies of the natural world. Like Lempert, who frequently organizes his photographs into associative “chapters,” visual motifs weave through Lange’s work. For example, spirals appear several times in Another Language. Near the beginning of the book, a spit of land juts out into water and then curls into itself. Later in the sequence, a solitary leaf, isolated against a seamless white backdrop, bends to form a circle. Toward the end one finds a whirlpool of large but indeterminate scale. Seen from above, the concentric rings of disturbed water call to mind satellite imagery of hurricanes.

The image of a whirlpool implies recursion, and Lange circles back to his favorite subjects. While in Tokyo in 2009 he created a series of flash-lit photographs of crows in trees, later publishing them as a book through his imprint Farewell. He revisited the subject on a later trip to the Japanese capital, and in summer 2015 published Citizen, a book of photographs depicting pigeons on the streets of London. Unlike his earlier crows, specks of black in a tangle of branches, Lange photographed the pigeons from behind with an estranging level of detail. The images offer a proximity and stillness we don’t often get in busy urban environments.

Lange’s techniques and preferred methods of distribution are likewise consistent. He uses a flash more often than most photographers working today, and the light gives his pictures a crispness and flatness that one rarely finds outside of party photography—a genre that could not be further removed from Lange’s tone and preferred subjects. And, despite the success of Another Language, published by MACK, Lange continues to self- publish. “My vision doesn’t end with the images themselves,” he insists. “I like to be in control of the packaging, the web presence … all aspects of the way I communicate.”

One of Lange’s current projects is a genre-crossing study of urban environments, from Tokyo to London to New York. It is tempting to think of this endeavor, after several smaller-scale series, as an urban update to Another Language. A stylized whirlpool, simpler than the one described earlier, appears on the cover of that book. In fantasy literature, a whirlpool pulls you beneath the surface and discloses to you a separate reality. It is an alternate realm to visit, explore, and—once transformed—leave behind. Lange’s talent is to discover that separate reality in the surfaces of our world—even the impenetrable, glass-and-concrete facades of our cities. Like all great photographers, he scrutinizes those surfaces, excising images that offer a truer, if indelibly stranger, version of what the rest of us see.