Carol Bove

Writing,This interview was published in, and featured on the cover of, the May 2012 issue of Art in America.

Carol Bove’s considerable reputation rests upon more than a decade’s worth of refined and culturally literate artworks. Her early sculptural installations, often taking the form of plinths or wall-mounted shelves laden with period books and knick-knacks, evoke memories of 1960s- and ’70s-era bohemianism, and the individual and societal soul-searching that accompanied the period’s wrenching social transformations. That many viewers have no firsthand experience of that historical moment and know it only through publications, films, and other cultural objects is part of Bove’s point. Born in 1971 in Geneva, Switzerland, and raised in Berkeley, California, she too experienced this cultural ferment at a remove, filtered as it was by the preferences of her parents and their milieu. Because of this, her ability to capture what seems like the essence of the era results as much from an understanding of how we construct history as from a feeling for the lived texture of the time. Her deft juxtapositions—of Playboy centerfold images, paperback copies of Eastern mystical writings and Western psychological treatises—both frame a worldview and reveal the act of framing.

Bove came to New York during the mid-1990s and graduated from New York University in 2000. She began exhibiting immediately thereafter, and her carefully calibrated arrangements of objects were widely acclaimed in the ensuing years. Bove has broadened the range of materials she works with, the forms her artworks take, and the historical antecedents she repurposes. Though “the ’60s” (a time not coterminous with the 1960s) remain a touchstone and one of the period’s emblematic art movements, Minimalism, a preferred aesthetic framework, today her art has been drained of much of its cultural specificity. Bringing together materials both luxurious (peacock features, gold chains) and rough-hewn (driftwood, steel), Bove has elaborated an aesthetic at once unique and capable of rehabilitating artistic precedents that have fallen into disfavor.

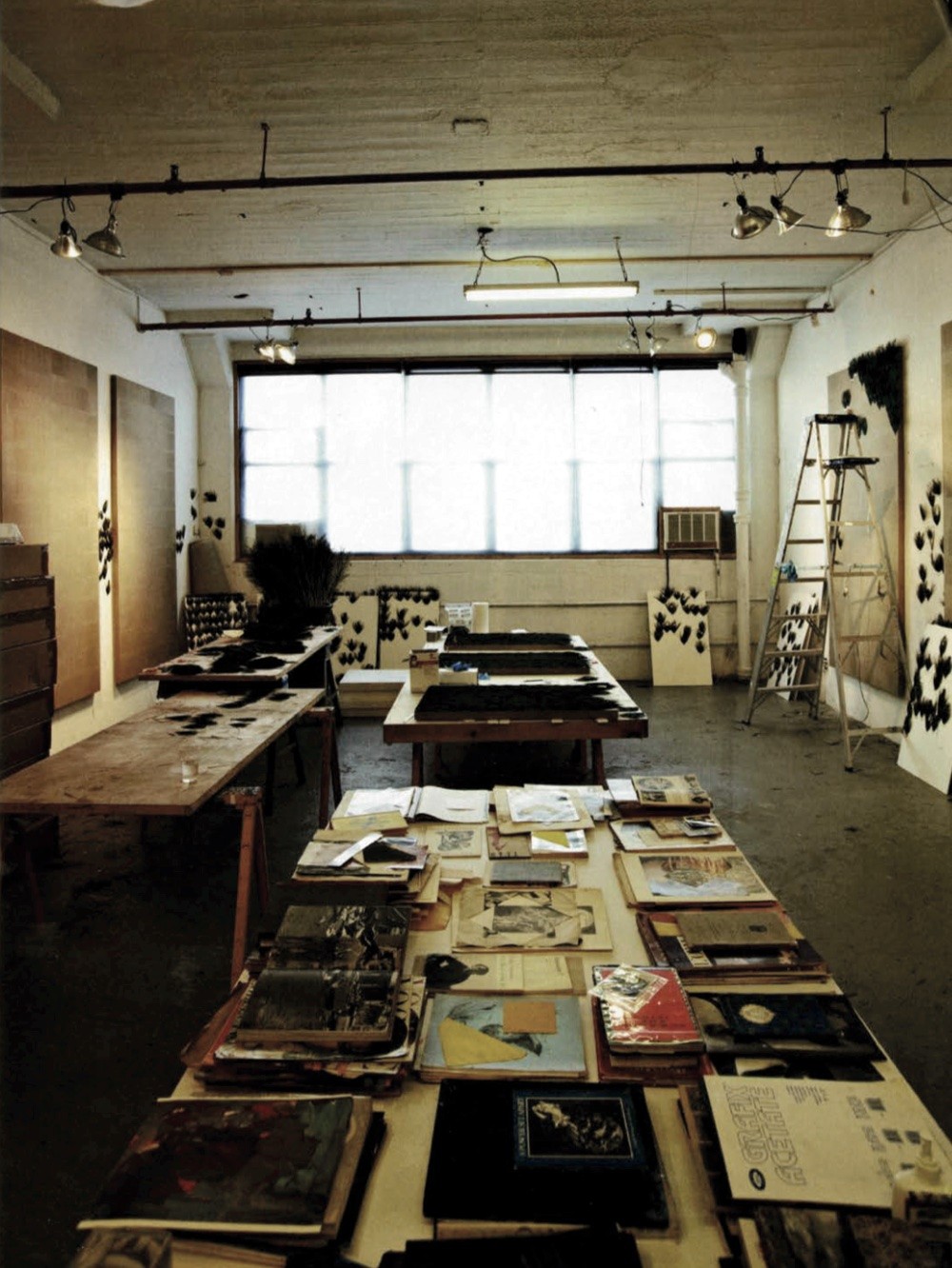

The artist works in a large studio a few blocks from the industrial waterfront in Red Hook, Brooklyn. The location is important: she scavenges urban detritus from her immediate environs, and produces work in collaboration with artisans whose machine shops are within walking distance of her building. AT present she is working on her first two large-scale outdoor commission. One sculpture will be exhibited in Kassel, Germany, from June 9 to September 16 as part of Documenta 13, curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. The other will be presented later this year at a New York City location that is yet to be announced. The edited trancript of our conversation, which took place at her studio in February, begins in medias res as Bove describes her plans for this latter work.

The installation [in New York] will have a platform featuring a totemic sculpture—a huge I-beam with a log attached to it. It’s a sixteen-million-year-old piece of petrified wood. At first glance it seems like a normal object; it looks like regular wood, so pedestrian as to be almost disappointing. Then, as you touch the material, you discover that in places it’s broken like a rock. You begin to understand what it is.

The platform has another element, my attempt at generic sculpture. I wanted to make something complicated, like tangled spaghetti, out of a material that has a different texture. That part will be made out of tubular steel and appear almost sinuous, though with an awkwardness because I’m making it out of half circles joined together. In a way it’s diametrically opposed to the petrified wood. It’s shiny, hard, smooth, industrially produced; its horizontal orientation balanced out the composition as well. I hope that this sculpture will engage the city in both material and temporal registers.

What has it been like to scale up your work and, given the unpredictable circumstances of the setting, to build for contingencies?

It’s totally, totally different from what I’m used to. Most of the time I’m very dependent upon everyone in the exhibition space taking care of the work, ensuring that no one touches things … and now I have to think about the work being rained on, or people climbing on it.

Is it difficult to accommodate yourself to that?

No, it has actually been stimulating to revisit my early experiences of outdoor sculpture, to realize how formative and exciting they were.

There is something fascinating about placing out in the world an object with no instrumental purpose, something provocative about the gesture.

In the past you’ve mentioned childhood experiences playing with the Arnaldo Pomodoro sculpture on the Berkeley campus.

Yes, the sculpture garden at the Berkeley Art Museum was very important to me. It does not exist now—I think because of earthquake concerns. Anyway, later I had the idea that outdoor sculpture was simplistic because of its need to be accessible, and now I’m realizing how wrong I was about that. There is something fascinating about placing out in the world an object with no instrumental purpose, something provocative about the gesture.

How far have you traveled along a path from, on the one hand, artworks that require knowledge of cultural references to, on the other, artworks that are easily accessible?

In terms of how I conceive of the work’s intellectual contexts, I don’t think there’s a big difference between my gallery shows and my new outdoor projects. In both instances I’m interested in the open-endedness of the situation. In an outdoor environment, especially one used for numerous other purposes, viewers’ initial indifference requires something different of the artist, a novel way to hook people. The benefit, of course, is that viewers don’t come to the work with preconceived ideas of what it should be or do. How can an artist communicate through a public artwork, even on an unconscious level? These are interesting questions to try to answer.

You’ve been conceiving this piece for New York at the same time as you’ve been creating a work for Documenta. Are they going to be on view at the same time?

That was the original plan; now I think they won’t.

I ask because I think of your exhibitions as exquisite compositions in which each work relates to every other work. Is that ow you’re thinking of them here?

Well, I hadn’t thought explicitly about setting up a circuit between the two sculptures. But I was thinking of them together. The work for Germany will be situated on the grounds of the Orangerie in Kassel and will follow their compositions strategy. Everything there is placed in a line, so what I’m created will be stiffly in line with another statue that’s already there.

And what kind of elements will it have?

It will have the same kind of elements [as the New York piece]: a totemic sculpture incorporating petrified wood, as well as another abstract component, this time a network of variously scaled cubes in bronze and steel. I want it to function for viewers at a distance and to have details fascinating enough to hold the attention of someone who has come closer to it. An additional platform I’m creating in this case, however, will stand apart from the rest of the work and have nothing resting on it.

Can you tell me a little bit about the Orangerie?

The venue is an eighteenth-century building with extensive grounds. Off to both sides of the main garden are hedged-in spaces i think of as outdoor rooms, in the center of which are statues. One is Apollo and the other is Flora. I wanted Apollo; I felt the Apollonian context would be a nice contrast to some of my works’ elements. But I didn’t get him. I’m OK with Flora, of course. It’s a strange space; it feels kind of metaphysical.

Has this been a rewarding enough experience that you would consider making more outdoor work?

Yes, it has been great, and I’m really into it. I’m exciting by having to work with the viewer indifference I described earlier. I have enjoyed making works that need to be complete in themselves, that don’t need an engaged viewer. It has seemed to me like an opportunities to try and communicate with the unconscious realm.

Can you discuss your relationship to Berkeley, where you grew up?

There are wonderful hills and parks in Berkeley, but I also always loved the city’s more industrial areas.

Near the water?

Yes. Even as a teenager, making artworks—my juvenilia, I guess—I was really attracted to industrial districts. I collected rusty junk. Decades later I realized, “Oh, I’m still doing what I did as a teenager.” The use I make of these materials is different but the impulse is consistent.

I have a kind of romantic attraction to liminal spaces. I feel they are underappreciated. They feel wild, and the lack of care for them is somehow attractive to me. Somehow I identify it with 1930s-era Farm Security Administration photographs—shabby America.

So it’s the atmosphere surrounding the materials more than the act of rescuing. You’re not a hoarder?

[laughs] No, I’m not obsessive-compulsive. I’m not a collector; I don’t like to hold on to things. I spend time with them and then allow them to continue their lives elsewhere.

Though it’s a very carefully thought out path that you set them on.

Right. For now, at least. But down the road they may end up unbecoming sculpture. I can imagine them losing their sculptural form. In a way, I build for this. My sculptures can and must be taken apart and then put back together. Disaggregation is important. Therefore, each element needs to maintain its individual identity, its autonomy.

The majority of the sculptures you’ve made are, right now, in a disaggregated state. They’re in museum storage or collectors’ storage.

They are resting [laughs]. They don’t have to be sculpture all the time. The ones that are put together, that are performing … well, knowing that they are out there takes some kind of energy out of me, psychic energy.

That’s perfectly understandable. Let’s return to the topic of place, this time Red Hook. Of all the neighborhoods in New York City in which I can imagine you living and working, this one seems most appropriate. It’s the most weathered, it’s an aging industrial waterfront. Is that important to your practice?

Yes, totally. Like the Berkeley waterfront, it’s another site of American industrial decline, which fascinates me. The neighborhood is separate from the rest of Brooklyn, divided from it by a highway; it functions as a kind of hideout. I wasn’t looking, but when I found the building in which I now live I immediately thought, “OK, this is my house.” A close friend from Berkeley saw it and said, “You’ve moved back to Berkeley.”

If you moved to another part of New York would your work change?

Probably. I worry about moving. My materials are so much a part of this particular environment. My processes are also specific to the particular fabricators whose shops are in this neighborhood. I feel very attached to where I am.

Do you adapt your ideas to the skills possessed by the craftsmen you work with?

Yes, I would say so. It’s not just Red Hook, but New York more generally. I sometimes make sculptures that look like jewelry, and in the jewelry district here you can get any thickness of chain, or get something plated—almost anything I need I can find here. I can also sell my metal scrapes and use the money to buy new materials; metals are convertible commodities in New York.

Sometimes when people hear the word “psychic” they think “flaky.” I’m interested in means of apprehension that are not necessarily anti-analytic but that are not routed through the intellect.

Your process is beginning to sound like managing a series of flows. Materials sometimes literally wash ashore a few blocks away. Some get made into artworks and enter another circuit, and the leftovers are eventually recycled.

It’s not all movement; there is also a lot of … well, maintaining. I take in more than I need, and things sit around together for a while.

There’s another side to your work that many people discuss, an aspect that is derived in part from its references to spiritual seekers or guides.

Perhaps this ties in to what I said earlier about the ability of public artworks to engage a different part of a viewer’s consciousness, because it requires a different kind of attention. Sometimes when people hear the word “psychic” they think “flaky.” I’m interested in means of apprehension that are not necessarily anti-analytic but that are not routed through the intellect.

A pre-linguistic understanding?

Not pre-linguistic or anti-linguistic or anti-intellectual. Just non-linguistic. Sort of like the process my work has undergone in the last few years, moving away from the inclusion of—or direct reference to—printed material. There are still cultural references, but it’s not as easy to discern a particular one.

That shift is in part because I don’t want my work to seem like a research project. One is rewarded for being visually literate and knowing about the culture that this material emerges from, but it’s not a game of figuring out how the different references relate to each other. I prefer the idea of “irresolvability.” I want my works to have a shifting identity.

So the new works are more vague? Though perhaps without the negative connotations associated with that word.

I want to recuperate vagueness. Sometimes I imagine myself as the first viewer, and I look for elements that cause me to think, “I don’t get that,” or, “That doesn’t do anything for me.”

In past interviews you’ve mentioned the Tibetan Book of the Dead, the I Ching, the Bhagavad Gita, the Kama Sutra. Plus many of the pocket paperbacks in your early work were translations of books on sociology and psychology by European authors. How conscious are you of bringing to bear upon your work an intellectual heritage that isn’t American?

It’s important, but I’m also interested in the American filter. I feel that you’ve phrased the question as if these were active choices on my part, but the intellectual culture in Berkeley when I was growing up was very international, very assimilationist. Many people living there and then were looking to other cultures for meaning. It can seem now like an impulse to get rid of everything in American culture. Every aspect of American ideology was being reevaluated, although in retrospect I can see how a lot of the dominant culture was reproduced unconsciously.

My first big sculpture show, in 2003, was called “Experiment in Total Freedom.” That was a kind of joke about the era, or at least my experience of it. Adults seemed so permissive: “You can do whatever you want!” As a child, I wondered, “What does that mean?” I feel I actually need a structure in order to do something. There is something kind of limiting about total freedom.

Cultural inquiry of the kind that went on in the Bay Area in the ‘60s is a process, and it could still be very exciting. Becoming fully conscious, you know, would be a great thing.

That cultural moment didn’t lat long, nor does it continue in many places today. Perhaps it’s not sustainable.

I hate to generalize about the period, or about the place. I’ll simply say that cultural inquiry of the kind that went on in the Bay Area in the ‘60s is a process, and it could still be very exciting. Becoming fully conscious, you know, would be a great thing. It would be great for many people today to engage with that idea.

I want to ask you about the legacy of Surrealism. Do you feel that the ideas about consciousness animating it ever truly broke on these shores?

In California—Berkeley, San Francisco—there’s a tradition of found-object assemblage, stuff that is almost naively inherited from the Surrealists. There was a kind of beat culture, exemplified by Wallace Berman, that seems like Surrealism plus the Kabbalah, which is an interesting formulation. My early experiences with art-making were through that instantiation of Surrealism. I was attracted as a young person to Bruce Conner’s work. If Surrealism did find a home in the US, I feel like that’s where it went—to California.

On the other hand, I sometimes wonder whether Surrealism is too silly for us. I don’t mean that dismissively; I love Surrealism. I think there is a lot of it in American art, but people don’t want to call it that because it sounds too silly. We have an aversion to, a squeamishness about, the unseriousness of the unconscious.

I can tell by this long table covered with books and periodicals that you spend time sifting through all manner of visual materails. What else are you looking at lately?

Right now I’m looking at Plop Art.

Pop Art?

Plop Art.

To learn how to be a public artist?

[laughs] Not to learn how to do it—just to see what’s out there. The art world is critical of it, but I’m finding much that fascinates me. Its relative disuse gives it a lot of … wilderness.

It’s unsupervised. You can explore it at your own pace.

I like that. Do you know [George] Gurdjieff? He thought that esoteric knowledge is almost like a material—a material of which there is a finite amount. If you have certain knowledge, you can’t just give it to everyone. If you share it, you are actually parceling it out. But if no one’s paying attention, well, that’s how a sculpture that’s in plain sight could seem like it has a wilderness. For people who do want to give it attention, it can give something back. All the material hasn’t been snatched up. That’s part of what I found interesting about the New York City project.

Do you suspect that people will figure out that part of the work is millions of years old?

I hope so. It has a lot of energy stored up in it.

Where did you find the petrified wood?

On the internet, of course. I went out to Washington state to pick it up.

At some point you decided that it would be OK to use materials that you didn’t happen across on the Brooklyn waterfront, or you didn’t find in a used bookstore. Was that a difficult threshold to cross?

I was aware of the transition. I had set certain constraints on my activities, and I had to ask, Is there a reason for the constraint? Or does it no longer serve me?

What is the constraint in your studio now, if there is one? Or does your studio practice replicate the freedom and chaos of your childhood in Berkeley?

I’m sure there are a lot of constraints but maybe there are so many of them that I don’t even know how to articulate them. I started with very rigid ones. At first I was only looking at issues of Playboy published between 1967 and 1972, or something like that. That was it. I couldn’t invent anything. I could photograph them or draw from them but that was it. I started off very confined, and have gradually loosened up.