For Organ and Brass 📬

On discovering, and obsessing over, faraway artistic communities—in this case music from Stockholm

For more than two decades I have spent a few hours each week, every week, seeking out and listening to new records. In high school, this involved sending a dollar and a self-addressed stamped envelope to punk-rock record labels for their catalogues, then mail-ordering what looked intriguing. In college, I would ride the subway to Harvard Square and shop at Other Music; the location closed not long after I graduated and moved to New York. Later, it was Napster, Limewire, and mp3 blogs, which I scanned from a series of outer-borough apartments, my headphones on to avoid upsetting roommates. Now I benefit from the ease and breadth of streaming services and the headphones ensure my kids don’t wake up.

About fifteen years ago, I came across and dove deeply into experimental electronic and jazz music from Norway, mostly released by the labels Rune Grammofon and Smalltown Supersound. The music was esoteric but not off-putting; many of the record covers featured charming designs by the artist Kim Hiorthøy. Here was a beautiful, flourishing creative community known to few people in New York—at least not the people I spent time with. When I first visited Norway in the spring of 2005, local artists were surprised by my obsession; I could talk not only about bands, but also about clubs I had never visited. I was later invited back to Norway to meet with many of these musicians and discuss a potential collaborative project in New York. The program didn’t happen, but I remain surprised and grateful that one day in 2007 I found myself above the Arctic Circle, having breakfast in Tromsø with Geir Jenssen.

It took more than a decade to fall down a similar rabbit hole. In 2017, I somehow came across a mention of Ellen Arkbro’s record For Organ and Brass. The title alone piqued my interest, and its description furthered my curiosity: here was an album performed on a seventeenth-century German organ chosen because the intervals and chords of its historical tuning resemble those of traditional blues music. I was hooked from the opening notes of the titular twenty-minute composition. It is slow-moving, textured, and challenging yet suffused with a rough beauty. It’s a sand dune. A glacier.

Unlike my Norwegian odyssey, this time more information awaited me. (Thanks, YouTube, Bandcamp, and Soundcloud.) I quickly discovered a coterie of classically trained experimental drone musicians in Arkbro’s circle. Some had even formed a Sthlm Drone Society that once performed in a mine shaft. They founded a record label, XKatedral, that releases cassettes with titles like “Tragic Chorus” in editions of one hundred. In her music, Maria w Horn, one of the XKatedral cofounders, “oscillat[es] between minimalist structures and piercing power electronics.” (Listen to “Fides Minus” for a breathtaking four-minute definition of “power electronics.”) Kali Malone, an American residing in Stockholm who has collaborated with Arkbro, creates “sonic monoliths” on pipe organs that are recorded from so close-in that you cannot hear the room’s reverb. Most impenetrable, to me, is Sand Circles, who posts pictures of plants, sunrises, and anonymous urban infrastructure to Instagram. Last year, he—I know it’s a he—released a track that has the most beautifully jarring transition I might have ever heard. Five and a half minutes in, the song descends suddenly into an auditory hell that is also, somehow, comforting.

Though I have watched interviews with and live performances by many of these musicians, a certain mystery remains. I don’t know what it’s like to be in a club—or, for that matter, a mine shaft—while they perform their astringent, harsh, soul-cleansing music. I can’t fully trace how they came to know and collaborate with one another. Despite my attempts to follow closely, I sometimes don’t find new tracks, remixes, and DJ mixes until they’re months or years old. That’s OK. In a way, I’m relieved to know that my addictive personality still bumps up against limitations, that technology cannot make the window entirely transparent.

But I also know, after my second such immersion in fifteen years, that technology also enables me to better understand something beautiful and strange when I come across it. Now I’m just waiting for a live date in Toronto.

Elsewhere

Click here for an hourlong Spotify playlist that encompasses many of these artists.

- As long as I’m discussing music, I should mention Tim Hecker, a Canadian musician now living in LA, who still holds the top spot—across all disciplines—on my list of favorite artists of the twenty-first century. I’d have trouble ranking his ten albums; they’re all that good. (And, coincidentally enough, he too played a live set in that mine shaft in Norberg.)

- Evan Caminiti is also somewhere near the top of that list. His music as part of the duo Barn Owl keeps me company years after it was released (despite my obsession with the new). The 2010 album Ancestral Star is the place to start.

- Last year, Helge Sten, the Supersilent member and dark prince of the Norwegian scene described above, revived his Deathprod moniker for its first album in fifteen years. Occulting Disk is “an anti-fascist ritual” of an album that Grayson Haver Currin rightly described, in Pitchfork, as “mesmerizing and terrifying.”

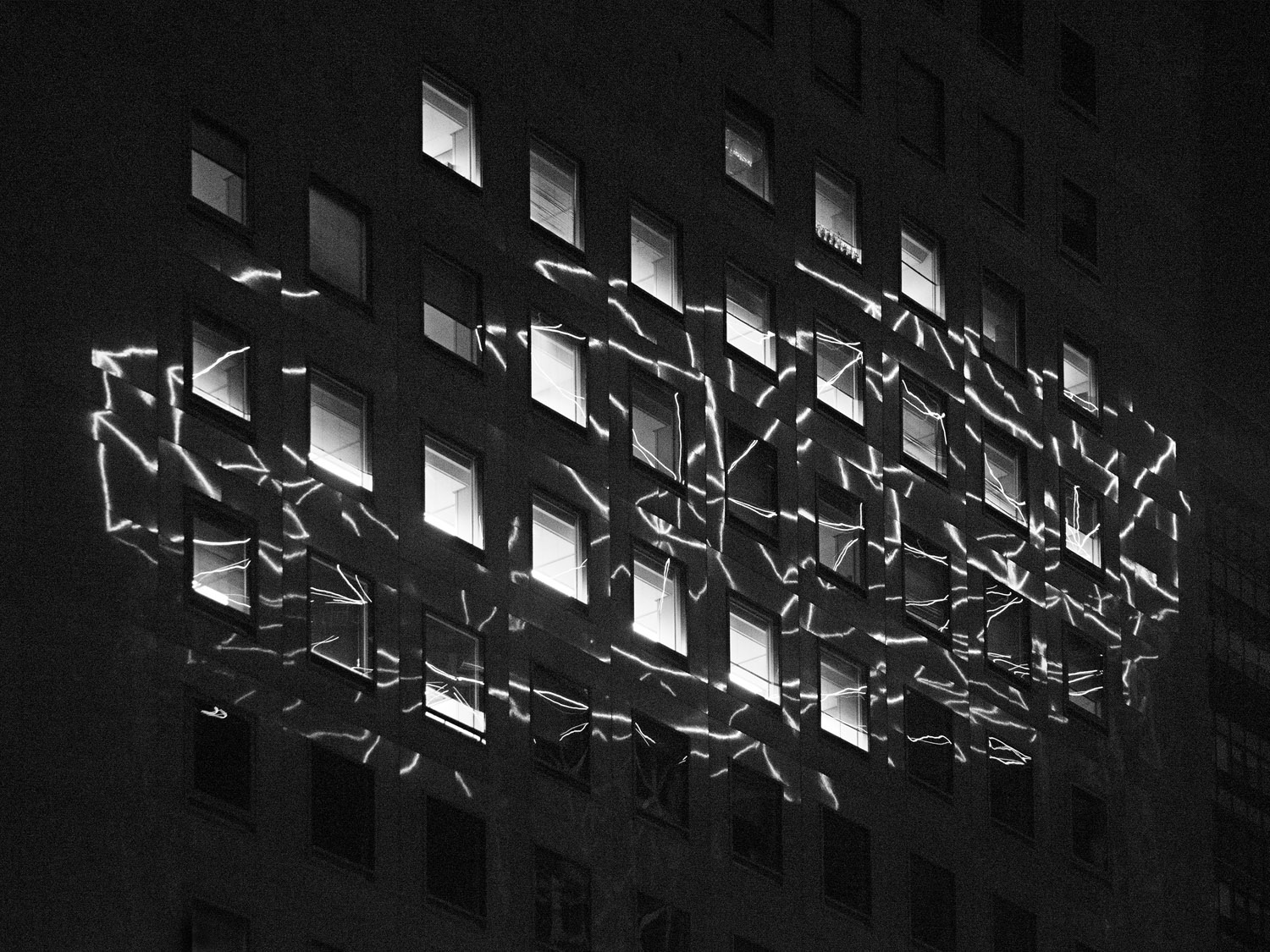

Photo: Mårten Lange, Facade Reflection, 2017.